|

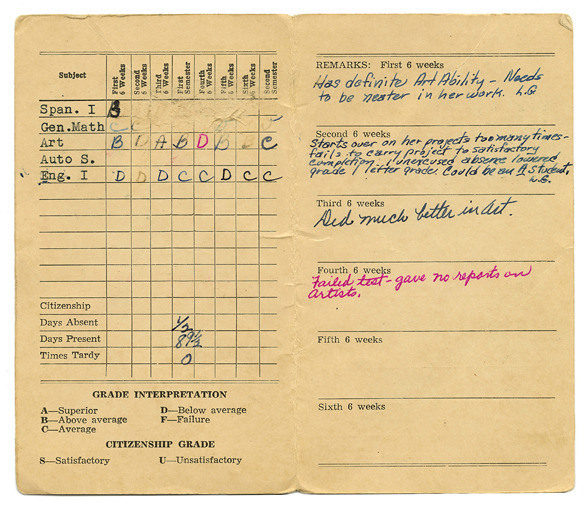

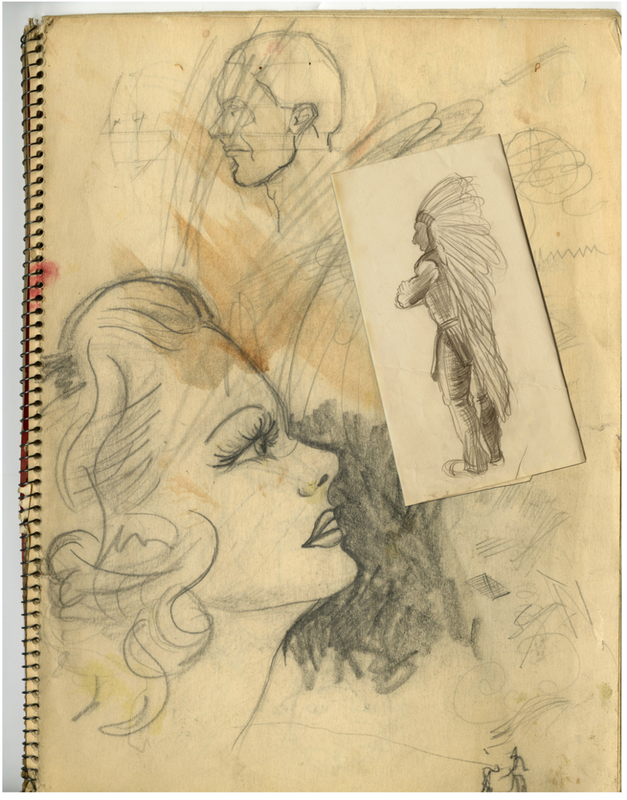

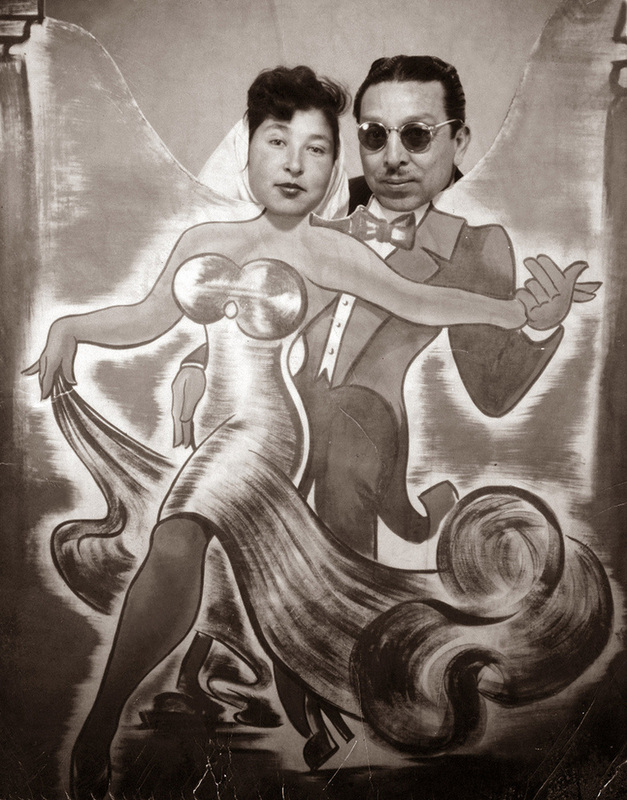

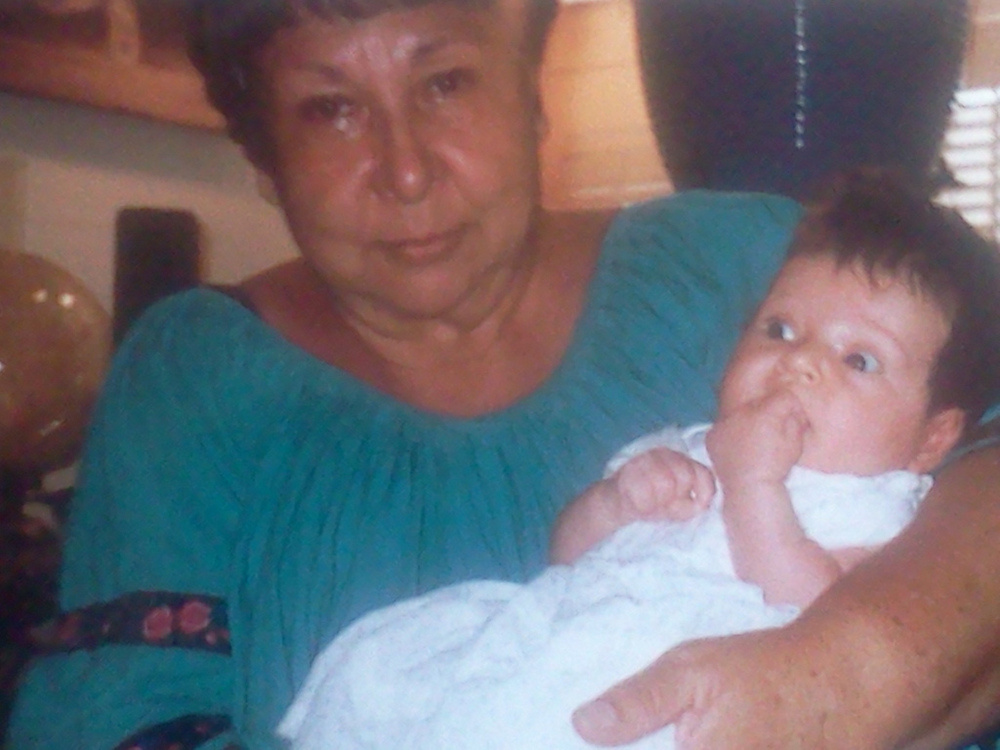

Nov 10 2011 For Liz Today would have been my grandmother’s 77th birthday. In her memory, here are two essays. One written by me. The other by my daughter — who is named after my grandmother. Pin-up Debt by Cate Mi Abuela/my grandmother. I owe her an enormous debt of gratitude. She gave me my neurotic disposition, my disdain for some and obsessive compulsive admiration for others, and the ability to swear like Joe Pesci. She provided opinions free of charge on topics ranging from UFOs to chupacabras and reincarnation. She was a maverick. Born in a small town outside of Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. Eldest in a Mexican family of nine children, she was expected of course, to care for her younger siblings. Her nature caused her to rebel, leading to her being sent to live with her grandmother. She married at sixteen, and by eighteen, with two small children in tow, moved to Southern California with her first husband. It was the early 1950s and she yearned for something greater. With courage and swagger, she hit Hollywood looking like the southwest’s version of Elizabeth Taylor. Soon after, she left her husband, abandoned her children, and posed for one of the first issues of Playboy Magazine, or so the legend goes. There are unmarked photographs remaining as documentary evidence, but no back-issues to confirm. Her Bohemian spirit led to painting. Her southwest inspired paintings would be collected by John Wayne and Shirley Temple Black. She would teach classes with Leo Politi and trade poses with other minor Los Angeles artists of the period. In early 1960, she was a regular at Hollywood hotspots like the Dresden Lounge and Morrow’s. This set the stage for her chance meeting with a long-haul trucker from Illinois, a man so smitten with her, that soon thereafter he left his wife and five children just to be with her. The two would finally marry in 1972, two months before her unwed teenage daughter was to give birth to twin girls. Her “angels,” my grandmother would call us. In a scene eerily reminiscent of her own life, our mother too would abandon us, leaving us at birth to be raised by my grandmother.We grew up under my grandmother’s patronage, benefiting from her sense of adventure, and very large Broadway department store credit card bill. Outfitted, fed, and pampered to the extreme, she wouldn’t hesitate to drive me and my friends to Melrose Avenue in search of Doc Marten’s or bright yellow Manic Panic hair color – though refusing to purchase the color until I switched to bright purple because it would “set better” with my skin tone. Her debt on our behalf was immense. Trips to the mall, Ballet Folklórico costumes, prom dresses, dental work, college tuition. It all went on the charge card. I could not understand it all when I was young, and perhaps not until her death, did I realize that she was trying to pay the universe back for all of her prior indiscretions. Though in her heart it felt like her monetary debt was never quite able to match her life debt of past regrets. Years passed and we grew up. Her painting style changed. Her work went from western landscapes and portraits to loose, impressionistic renditions of trees. The same tree. Over and over and over again. This was the first hint of the Alzheimer’s. There were other signs, too. She began to sit and chat endlessly on the porch with the Jehovah Witnesses that came to convert her. Before the Alzheimer’s she couldn’t stand them, and wouldn’t hesitate to tell them so. Now she would either out-talk them, constantly repeating herself, or they would promptly leave when she asked them if they wanted their Tarot cards read. She would pay the neighbor kid ten bucks to wash her car, which he gladly did three times a week because she would forget that he had already washed it. When she could finally no longer paint, she would gather sticks and safety pins and arrange them in freakishly marvelous ways. I named my daughter after her. They would share the same traits, both beautiful and artistic. Later, when my grandmother was deep into her hallucinated mind-wasting madness, my daughter would be the only person she would be able to recognize. Her long-haul trucker husband, her twin angels, and her namesake were at her side during her last days in this world. She was in a coma, nurtured slowly towards death by way of palliative Hospice care. Liz and her great-granddaughter I had a Jungian therapist who once told me that we are put on this earth to pay the debts of our grandparents. I feel the weight of this debt. Debt that has been demanding to be set right over the course of oh so many generations. I am left with the thought that we can never really resolve the debt to others; we can only build karmic debt within ourselves. Mi abuela, Liz, passed away from complications of Alzheimer’s November 14, 2010. Essay: Mi Abuela by Cruz When I was younger, I remember our long car-ride to my family’s ancestral city in a small, rural part of New Mexico. The roads got smaller, and my mind expanded, eager to carouse with my cousins, and taste the best homemade Mexican food in the little town: Sopaipillas, red chili, and fluffy tortillas. As my imagination roared, and undoubted innocence peered through my brown eyes, I could not yet grasp much of what I heard. But despite my youthful perspective, there’s one thing to this day I remember my mother telling me on that unending ride.“You were born the last of five living generations of incredible women,” she said; and I looked up at my four elders, in that house overflowing of family members. I looked up at those four women, seeing nothing less than incredible. Each and everyone of my grandmothers had an impact on my life, but the most significant, had to be my Great-Grandmother, Elizabeth. My grandma is the strongest, most beautiful, craziest, and artistic being I have every had in my life. There is nothing I loved more than spending time in her unique home, listening to her wacky stories, and walking back and forth down that pine-tree shaded street in East-L.A. Thinking back now, the single year between these memories with her, and when it all came crashing down, dragged on like an endless road. My grandmother’s Alzheimer’s got the best of her, and wacky stories transformed into slurred speech and frequent drives to the house that no longer felt like a home. That crushing experience transformed me as a person; but it also helped me realize so much about my family, and about myself. Me with my great-grandmother and Jana the dog. My grandmother was beautiful. A Latina Elizabeth Taylor. Photographs of her model days of 1959 hang in my home. Her dark curly hair just like mine, and radiant smile brighten the photo. “Liz” always incorporated her artistry with her fashion sense, never dressed down, and applied her exaggerated eyebrows and pink lipstick until she was well into her seventies. She never gave up. Her spirit would never wane. Married at sixteen, and divorced two years later, Liz set out to pursue a career in Hollywood. A woman known for always speaking her mind, never overlooking an adventure, and incorporating her eccentricities into her artwork — though I never knew her that way. As I grew older, the Alzheimer’s progressed, I came to recognize it was no longer just her aberrant nature. She started slowing down; forgetting my name, singing songs whose lyrics didn’t make sense. Our visits became more frequent, my mother tense, my Grandpa with a countenance of denial and confusion. I remember the throbbing in my head listening to the discussions while sitting on that over-worn bench on the front porch. They wrung their hands and held back tears as they debated her well-being. I sat there and just held my grandma’s hand, wanting it all to miraculously be better, but knowing that wasn’t an option. A foreboding phone call gave me a glimpse at what was to come. I still hear the voice message my mom left me, her tone over-wrought, with her voice cracking at each syllable uttered. She needed to drive up to Los Angeles unexpectedly, my grandma had an accident. I was reassured that everything would be okay, but I knew it wasn’t. Staying at a friend’s house that evening, the night seemed to drag on endlessly, as I tossed in bed. Each turn bringing confusing thoughts and anxiety striking me in the heart. I stayed up late with endless thoughts for the worst, and anticipation of my mom’s hourly updates. Feeling lost and scared of what was happening, I questioned why I wasn’t there. She’d been hit by a car, my mom stuttered over the phone. It was concluded that she had wandered into the street in a state of dementia, her Alzheimer’s detrimental to her fate. She was admitted to a geriatric ICU for two-weeks and released with conditions set by the doctors. The doctor said she would be okay, but their home-life would not be the same. We knew my grandparents couldn’t live alone anymore. It wasn’t safe, unless someone was there with them. But complicating matters, my mother was not their legal guardian. Drives to their house became weekly. Stays at various hotels, and complicated conversations with family members became normal. Decisions were made by a long-absent daughter, and their home was cleared out. Grandpa would suffer a stroke as a result of the high-altitude they were hastily moved to. Eventually their recovery would lead them to a small board and care convalescent home in the backwoods of Roseville, California, five hundred miles away from their home. Grandma was pampered by the caretakers, and passed the time whistling on the couch and muttering about her days in the Wild West. They were settled in this seemingly safe place with alarms on the doors, and recently graduated nurses always on their feet, but they weren’t at home. We drove up as often as possible; sitting through quiet lunches of cheap steak and mixed emotions at the Sizzler up the road from their care facility. Tears welled up, but creased foreheads relaxed. I held my grandma’s hand as we all sat in comfortable silence. Despite the new environment, I still had Grandma, but apprehension ate at my soul, and thought about the future deep inside of me was only waiting to surface. The first time my great-grandmother held me. I don’t remember crying once. At the time, I didn’t feel the need to. The rush of it all came so suddenly, and I never took the time to realize it’s severity. If perfect existed, in my eyes, she was, and perfect could never disappear, could it? The doctor said she had blood clots in her brain. They’d formed when the car hit her, and remained inside of her untreated for all those weeks. When her body started slowing down, medical practitioners concluded it was fatal. Her speech started to come in a small whisper, like a coarse piece of sandpaper, until it stopped all together. Her eyes opened small and fluttered constantly, and then they were shut. It was one of those words heard on tasteless mini-series on television, but it never sounded as real as it did when it came out of my mother’s mouth. “…a coma,” she said. I ignored it, praying it wasn’t true. The cold waiting room chairs were my bed on those late nights at the hospital. My mom and her twin sister sat with my grandmother in the small room, but I didn’t want to see her, not in the state she was in. She wouldn’t look the same, and I didn’t want to lose the flawless image I had of her in my mind. A few days later, tests confirmed there was no coming back, no miracle recovery, and no breakthrough surgery. They moved her back into the convalescent care her and my grandpa knew as home, and she was placed into Hospice care. Ladies in white put her in a medical bed next to their old one, and placed a machine with strange tubes that made soft, synchronized beeping noises. That’s when I finally went to see her. She was barely there. Her usually olive-colored New-Mexican skin was pale, and her eyes were shut. Her overworked, delicate hand of 79 years was in my mother’s. My grandma lay in peace as a priest came and said her “Last Rights.” He placed a small beaded crucifix in her left hand. She was quiet in her never-ending sleep, but she still held on. My mom and my aunt, two of my elders sat next to me, and she, my fourth laid there breathing crudely. “We all love you, Grandma. Your family is here, and we love you.” My mother whispered with wet eyes. “You can let go.”  Our hands. We used to dig for treasures in her junk-filled room. On November 14th, 2010, my grandmother lost her battle with Alzheimer’s. There wasn’t much left of her. Her eccentric home in East L.A. was emptied of its capricious nick-knacks, and what little was brought to Roseville was dispersed among family members. With me, she left a gaudy box of 1950’s costume jewelry, a small vibrant-colored painting, as well as the backbone, dauntlessness, elegance, and modesty that had taken her so far in life. It took my grandmother’s passing for me to realize the inheritance she’d truly left with me. It had taken 12 months of undeniable struggle, and everlasting grief for me to understand. Now, with almost a year since her passing, I regret not spending that moment to tell her how much she meant to me. I can only wish to go back and explain to her that she was this undefined perfection that has made me the person I am. From this experience, I have learned the importance of family, the significance of life, and how easily it can be taken away, and I have come into touch with the person I am and the person I want to be. Now, in a world of billions, in a small town, and in a tight family of incredible women, I have decided to live the legacy my great-grandmother did, and to strive to be all that she was and more. |

Archives

May 2015

|